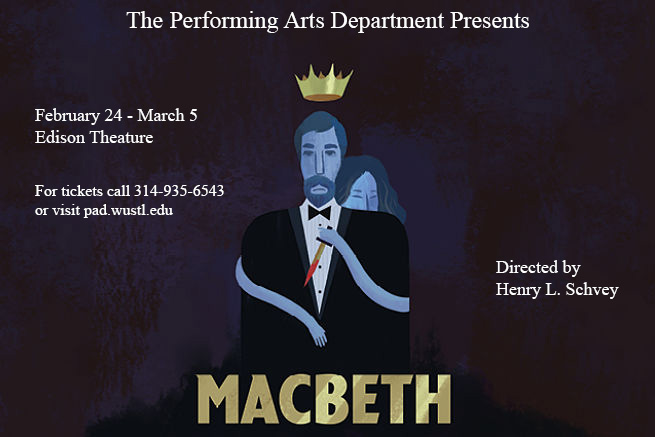

“Macbeth” begins at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, Feb. 24 and 25, and at 2 p.m. Sunday, Feb. 25. Performances continue the following weekend, at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, March 3 and 4; and at 2 p.m. Sunday, March 5. Tickets are $20, or $15 for students, seniors and Washington University faculty and staff, and $10 for WashU students. Tickets are available through the Edison Theatre Box Office. For more information, call (314) 935-6543

Read more about the production in this preview from WashU’s The Source:

The war is won, the enemy vanquished, the victors basking in glory. And then it all goes wrong.

“For many years, I saw ‘Macbeth’ as a story of good and evil,” said Henry Schvey, professor of drama in the Performing Arts Department (PAD) in Arts & Sciences, who will direct the Shakespeare classic in Edison Theatre beginning Feb. 24.

But as he prepared for the production, amidst the turmoil of the 2016 presidential election, “the play began to strike me differently. It felt more ambiguous, less black-and-white.

“It seemed a story of moral corruption.”

Guilt and doubt

Background, “Witches”;

Hannah Marias, left;

Brandon Krisko, center;

Sam Gaitsch, right.

Photos by Joe Angeles/WUSTL Photos

Traditional readings of “the Scottish play” emphasize the role of Lady Macbeth in pushing her husband to assassinate King Duncan. But to Schvey, who is setting the play in modern dress, this elides the complexity of both the characters and their marriage.

“The murder emanates from their relationship,” Schvey contended. “If you read the text closely, it’s clear that killing the king has been in their thoughts. Perhaps it was a plan, perhaps it was just an outlandish idea. But when she pushes him, it’s towards an agenda they’ve tacitly agreed upon.

“Macbeth is not a cardboard villain,” Schvey added. “He’s ambitious, a political force, but he’s also plagued by guilt and doubt. And his journey is deeply complicated. It’s not just about the rise and fall, the winning and losing. It’s about succumbing to temptation, and the deep futility he feels afterwards.”

At the same time, “Macbeth is operating in a world of flawed people. Macduff, who often is presented as a hero, takes flight, thus allowing Macbeth to butcher his family. Malcolm, Duncan’s heir, was born to royalty but not necessarily groomed to take the crown. Their shortcomings suggest a world in which there are no moral absolutes, powering Macbeth’s own ambitions.

“I think this aligns all too well with our current political moment,” Schvey said. “The world of moral ambiguity asserts itself in the play’s opening moments and never relinquishes its grip. It is a world of fog, in which the only certainty is that things are profoundly uncertain.

“For Shakespeare, whether or not Macbeth is a good ruler is almost beside the point,” Schvey added. “He’s more interested in the psychology of power. And at some level, I think Macbeth knows that, in killing Duncan, he’s killing the best part of himself.

“It’s a moral and spiritual suicide.”