The good, the bad and the bottom line: Balancing productivity and behavioral incentives

- December 18, 2019

- By Kurt Greenbaum

- 3 minute read

For Lamar Pierce, the subprime mortgage crisis and the Volkswagen emissions scandal are quintessential examples of how poor productivity incentives can drive misbehavior—the sort of misbehavior that crosses ethical lines and hurts people.

Homebuyers had incentives to lie about their credit worthiness. Lenders had incentives to originate bad mortgages. Real estate agents had incentives to smooth over red flags. The result: When the subprime mortgage industry collapsed, millions lost their homes. The crisis precipitated a global economic recession.

When VW hitched its wagon to low-priced, high-performance diesel cars—but couldn’t deliver—executives had incentives to build software that cheated the system. It was “a decision that probably killed 4,000 people,” Pierce said recently, citing calculations by environmental economists.

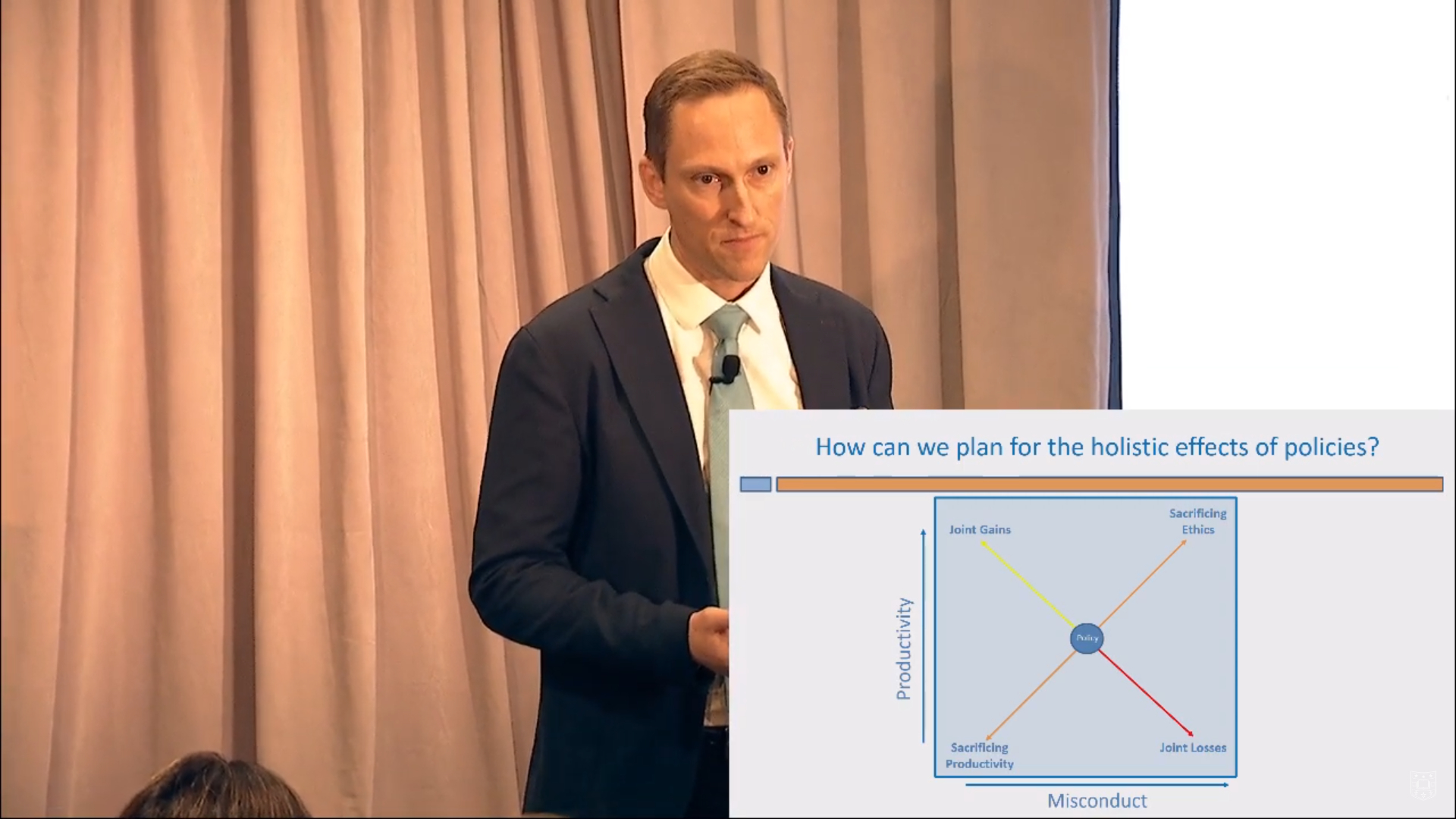

Pierce, professor of organization and strategy at Washington University’s Olin Business School, used the examples to illustrate the way productivity and misconduct can sit on the X and Y axis of any corporate policy or decision—decisions executives must grapple with every day. Pierce gave an overview of this decision framework in a talk on October 29, 2019, at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, entitled, “The Good, the Bad and the Bottom Line: Aligning Ethics and Productivity in Organizations.”

“Productivity and misconduct are not separable issues,” Pierce said.”

I consistently see managers trying to solve a productivity problem or solve an ethics problem—and being shocked when it creates other problems they didn’t anticipate.

Lamar Pierce

Schools heavily incentivize students to succeed academically in order to get into college, Pierce said, and then are shocked when they learn students cheat. Supermarket chains implement zero-tolerance policies to stamp out employee theft, then wonder why employees hate them and turnover is exorbitant.

“This doesn’t mean there’s no personal responsibility,” Pierce said. “But if you see systematic problems, you have to ask yourself: Is this about how 95 percent of your employees are bad apples or you don’t know how to manage them?”

Creating policies that incentivize both productivity and good behavior are very hard to find. In contrast, creating policies that sacrifice both are not. The sweet spot: Developing policies that sacrifice a tolerable amount of both productivity and good behavior. For example, Pierce argues that the optimal amount of employee theft is not zero. At some point, the cost of eliminating it may be higher than it’s worth.

Pierce offered four guidelines when framing policy decisions.

Define ethical bright lines.

What lines cannot be crossed? What behaviors can never be justified by productivity? Sexual harassment likely falls into that category, for example. Know those values in advance.

Anticipate gaming, shortcuts and cheating.

How might productivity incentives motivate bad behavior? Anticipate what might happen—then consider whether your organization cares about that outcome.

Anticipate motivational issues.

How might policies to address bad behavior—like crushing employee theft, zero tolerance for tardiness or digital surveillance—motivate or demotivate employees? If you’re committed to addressing sexual harassment, but only require employees to watch a 30-minute online course, what message are you really sending?

Ask what tradeoffs are tolerable.

“There are very few perfect solutions,” Pierce said. Can you trade a little bit on one dimension (decreased productivity) for a lot on the other (better behavior)? “Acknowledge that people are not purely rational,” Pierce said. “Acknowledge bias and complexity when designing policy. Humans care about few things more than fairness—and they have incredibly inaccurate views about what’s fair. Plan for those people.”

Leadership Perspectives

Olin professor Lamar Pierce speaks to the way ethics & productivity go hand in hand in the workplace.

Media inquiries

For assistance with media inquiries and to find faculty experts, please contact Washington University Marketing & Communications.

Monday–Friday, 8:30 to 5 p.m.

Sara Savat

Senior News Director, Business and Social Sciences