Detailed information about grocery inventories could enable dynamic pricing

- July 24, 2024

- By Suzanne Koziatek

- 4 minute read

Dynamic pricing is everywhere, from airline and sports tickets to Uber rides and items on Amazon. But what if a grocery store owner could use it to lower the price of a gallon of milk as it gets closer to expiration?

This approach could provide a “win-win” for grocers and customers, said Naveed Chehrazi, assistant professor of supply chain, operations and technology. Owners could sell soon-to-expire goods at a lower price, rather than allowing them to sit on the shelf to spoil. Customers could get a bargain on food that is still good to eat. It could even lessen the environmental impact of food waste, a contributor of greenhouse gases.

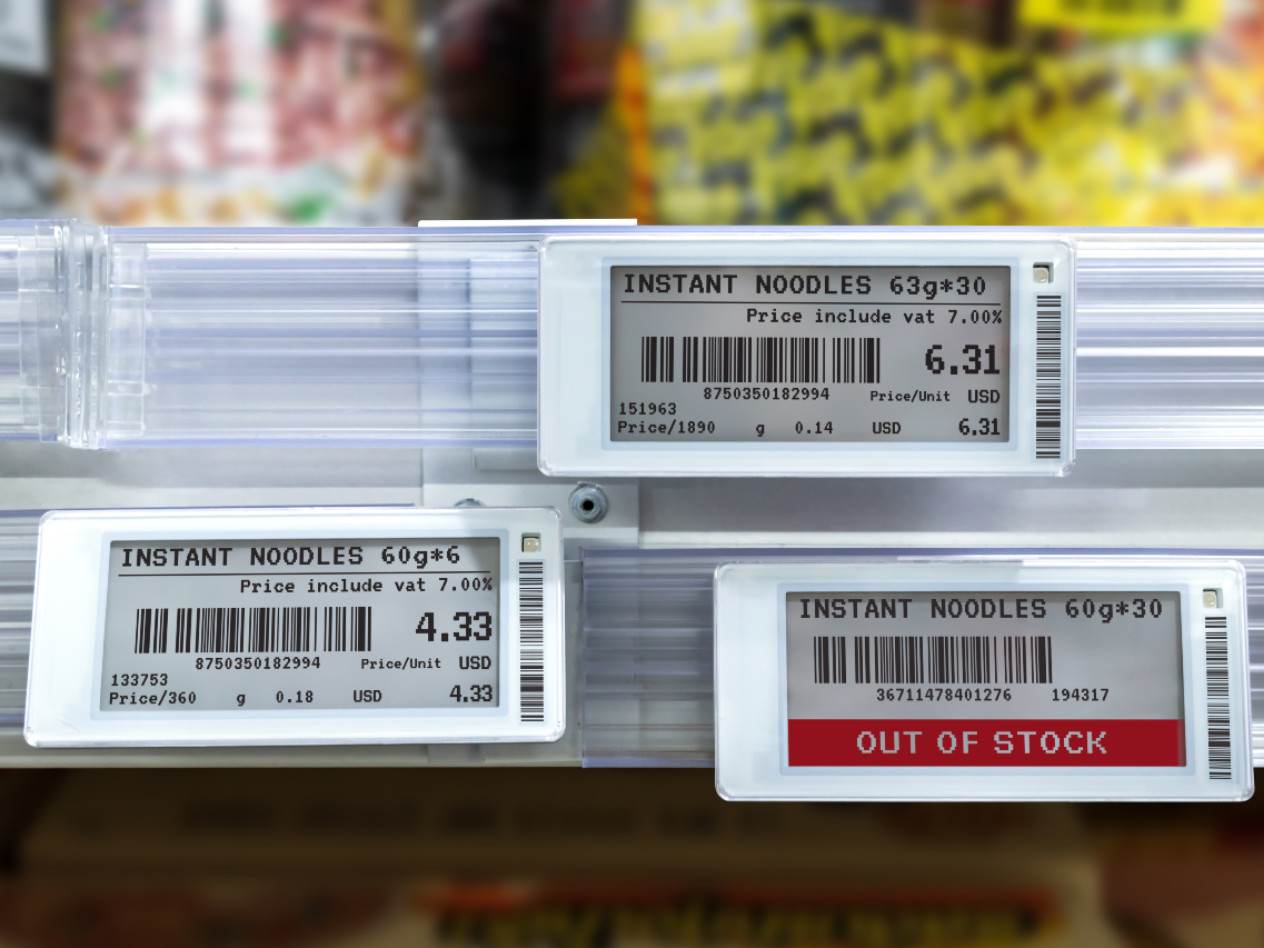

Many grocery stores have introduced technology that could enable dynamic pricing, particularly electronic shelf labels (ESLs), small digital screens attached to shelves that allow stores to change prices without the burden and expense of updating them by hand. This eliminates what’s called the “menu cost,” or the costs associated with changing prices.

But there is still a complication to making the dynamic pricing switch: Incomplete and/or inaccurate information about how much inventory a seller has, and how close it is to expiring. In a paper accepted for publication in Marketing Science, Chehrazi and his two coauthors show that this inventory information gap is the biggest obstacle to using dynamic pricing to sell perishable groceries.

They show that closing the gap—for example, using extended, individualized barcodes that include expiration dates—allows sellers to change prices far more frequently, as they react to changes in inventory.

If you have an item-level history of a product, when you scan it at the cashier, you know that you sold that gallon of milk that you received two weeks ago, and it was about to expire two days from now. This reduces inventory record inaccuracy. You have visibility at the item level.

Naveed Chehrazi

The paper, “Inventory Information Frictions Explain Price Rigidity in Perishable Groceries,” was coauthored by Robert Evan Sanders of the University of California San Diego and Ioannis Stamatopoulos of the University of Texas at Austin.

Testing inventory innovations

To test the impact of this technology, Chehrazi and his colleagues looked to Europe, where it is more common. They ran experiments at two grocery stores—one in the UK that introduced ESLs, and one in the EU that began using both ESLs and expanded barcodes.

The team tracked how many price changes were implemented at the store before and after introducing the technology improvements.

After introducing electronic shelf labels, price changes at the UK store increased by 54%. During a comparable period after incorporating both ESLs and expanded barcodes, the number of price changes logged by the EU store increased by 853%.

“What we propose here is that the reason that retailers do not experiment and do not practice dynamic pricing is because of inventory record inaccuracy,” Chehrazi said.

That inaccuracy may consist of actual errors in the data. “The (store’s) inventory record does not reflect what is on the shelf. Your record says there are 20 (of a particular item) and in reality, there are 10, or maybe there are 50,” he said.

The other factor is the expiration dates of the items. With a typical bar code, a retailer only knows how many items are in stock, but not how many of those items are due to expire over the next few days or weeks.

Expanded barcodes alleviate that problem, by showing a retailer exactly which items have been purchased, as well as the expiration status of the remaining stock. That gives them the information they need to adjust prices.

Aiding consumers, protecting the planet

Chehrazi said grocers’ profits from dynamic pricing are gained by reducing waste, not charging customers more. In fact, most price changes are in the form of discounts of varying depth and work to the consumer’s advantage, he said.

The waste reduction part of the equation also may benefit the environment. Unused food rotting in landfills produces greenhouse gas emissions, notably methane. This can account for upwards of 8 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“Just to put this into context, global shipping contributes 3-4%,” Chehrazi said. He said grocery store improvements wouldn’t eliminate those waste emissions entirely but could reduce them.

He noted that economic studies suggest that price rigidity (or the lack of price changes) can make recessions worse. Cutting prices swiftly in downturns can save stores money from avoiding food waste, while responding to recession-driven bargain hunting.

One obstacle to larger adoption of dynamic pricing is that its benefits generally go to the retailer, while the producer is responsible for tagging products with barcodes. Producers, meanwhile, don’t want to invest in extended barcodes unless they can also gain some benefit, either in terms of more orders, exclusive access to the retail chain, or explicit cost sharing. The authors of this paper suggest that policy makers can play a role in aligning the two parties’ interests by incentivizing or mandating the technology transition.

Media inquiries

For assistance with media inquiries and to find faculty experts, please contact Washington University Marketing & Communications.

Monday–Friday, 8:30 to 5 p.m.

Sara Savat

Senior News Director, Business and Social Sciences