Olin study shows upcoming appointments affect how we use time in the interim

- July 27, 2018

- By Chuck Finder

- 3 minute read

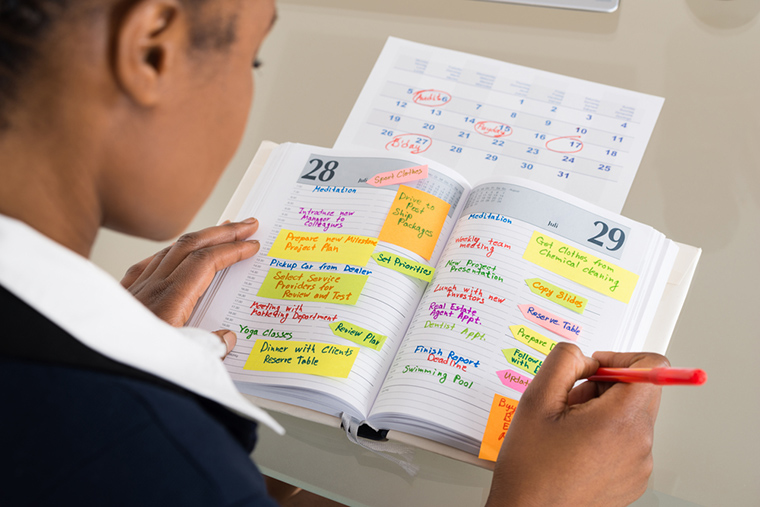

Consider the parent playing the role of air traffic controller with his or her child’s busy schedule.

First, there is homework for the kid to finish in the next hour. Then comes soccer practice followed by a piano lesson for the ensuing two hours.

“If the parent knows the deadlines and the kid just does their work, it’s the best of both worlds,” said co-author Stephen Nowlis, the August A. Busch Jr. Distinguished Professor of Marketing at Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis. “But if the parent is trying to get work done on their time …

“The big picture is, setting all these deadlines seems like a good idea. But too many deadlines makes you use your time less efficiently.”

That was the central finding of an eight-test study published May 15 in the Journal of Consumer Research titled, “When an Hour Feels Shorter: Future Boundary Tasks Alter Consumption by Contracting Time.” The boundaries in question are upcoming appointments, meetings, tasks, etc. And the researchers found that people facing them: (a) perceive they have less time than in reality; (b) perform fewer tasks as a result; and (c) are less likely to attempt extended-time tasks that can be feasibly accomplished or more lucrative.

The big picture is, setting all these deadlines seems like a good idea. But too many deadlines makes you use your time less efficiently.

—Stephen Nowlis, August A. Busch Jr. Distinguished Professor of Marketing at Olin Business School

When up against such an upcoming appointment, people tended to procrastinate on the long-time chore such as writing that report and reverted to working on shorter-time tasks, as in making a work call or typing up a quick synopsis. Or they’d skip both entirely to focus on the simplest of work forms, like answering emails … or scheduling more boundaries.

“It’s something we can all relate to,” said Nowlis, who started this project when co-author Gabriela N. Tonietto of Rutgers was a PhD candidate at Olin and co-author Selin A. Malkoc of Ohio State was an Olin colleague. “It could be anything. You have a deadline, and what do you do with your time? We don’t think about it as much from the perspective of consuming it, but, realistically, time is something we probably consume as much if not more than any other resource. So how are we consuming our time?”

The researchers conducted more than eight tests over a two-year period beginning in 2015 involving 2,300-plus participants to see how people in various situations arrived at budgeting scheduled and unscheduled windows of time. Among the tests included in the Journal of Consumer Research study were:

- Using the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) survey platform, 200 participants — split evenly between those with an upcoming appointment and those with a free schedule — were asked to pick between a 30-minute chore paying $2.50 and a 45-minute chore paying $5. They had an hour’s time. But the participants with an upcoming appointment felt they had 7.82 fewer minutes in their hour to commit to their chore than the people with an open schedule.

- At Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, 134 passengers were asked to take a 15-minute survey — about half of the passengers had 30 minutes before boarding, the rest had one hour. Some 26 percent of the people facing a shorter window agreed to participate, compared to 46 percent of the passengers with four times the allotted survey window.

- At Washington University, 158 undergraduates were told they had either a strict, five-minute window until their appointment or an implied boundary with “about five minutes to do whatever you want.” In the same five-minute period, the latter group accomplished 2.38 tasks compared to 1.86 tasks by the hard-timeline group.

“How do you best manage your time? How much scheduling do you need?” Nowlis said. “These are interesting questions.”

Their study provided some answers for trying to prevent issues. Basically, it counsels people to schedule wisely: Maybe leave a chunk of the work day open to accomplish extended-time tasks.

“If you have some big tasks, too many scheduled things will affect your productivity,” Nowlis said. “A lot of scheduling is fine for shorter tasks.

“So find the environment that works for you.”

This piece ran originally in The Source from WashU public affairs.

Media inquiries

For assistance with media inquiries and to find faculty experts, please contact Washington University Marketing & Communications.

Monday–Friday, 8:30 to 5 p.m.

Sara Savat

Senior News Director, Business and Social Sciences